Memento Mori

The worst night of my life took place when I was 11 years old. The doorbell woke me, and as I lay in my bed in the dark, I heard the deep voice of a man, followed by the screams of my mother. An officer was reporting to her the deaths of her sister and brother-in-law in a horrific auto accident. Their two children, my beloved cousins, were in critical condition, in separate hospitals as a result of the triage of the numerous victims. That was in 1961. Over 50 years later, the fallout from that accident still affects my family.

My aunt Cora was already a grandmother when this accident occured. She had eight brothers and sisters living. But my grandmother--her mother--never got over the loss of this child. Babu, as we called my grandmother, was a Polish immigrant who didn't speak English or work outside the home. One of her newly-arrived cousins, according to old country tradition, got permission from the funeral director to view the closed caskets before the wake and snapped some memento mori images of the horribly disfigured corpses. These he gave to my grandmother. Where she hid them, nobody ever figured out, but frequently she would be found in her bedroom, weeping uncontrollably, and we knew she had been looking at the pictures. Other than cursing that Polish relative, for over forty years no one ever spoke of the accident or of my aunt and uncle.

These days we know a bit better. There's no virtue in that rigid silence. My poor cousins were deprived, not only of their parents, but of the many happy memories of them we might all have shared, and of the healing and consolation which speaking about them and that horrible night would have brought. For most of her life, my girl cousin blamed herself for the accident, because she had wanted to go on the excursion which turned out to be fatal. Decades passed before she learned from older family members that her parents had planned the trip before she even mentioned it. Nobody even knew the guilt she carried in her heart, because everyone was too busy "sparing" her the difficult memories.

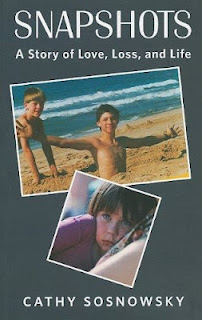

British Columbian college professor Cathy Sosnowsky has lost, not one adult child out of nine, but all four of her children. One, before birth, to abortion. One, a gregarious and well-adjusted teen, to accident. Two troubled adopted children to the streets. (The latter are alive, but estranged, and one is in prison.) She coped the only way she knew how, by writing about it, all of it. First poems, then this book called Snapshots: A Story of Love, Loss, and Life.

The title is a literal one. Sosnowsky has assembled over 50 family snapshots, and she organizes the book around them, talking about each one in turn. The pictures start before the children are born and continue after they're gone. The story zigzags from Canada to Europe and back, to pretty much all over the world as the author seeks the "geographic cure." Although we're treated to intimate details of the kids' lives, it's not just a story about them, but about an entire family with very complicated dynamics.

Writing probably saved this woman's life...or at least her sanity. And her book is useful to us, perhaps, too. The stories of others help us to piece together our own stories. Written stories are especially useful because writing allows the opportunity for reflection and organization which speech does not. Everyone has experienced some loss, whether of life or health or love or ambitions.

Sosnowsky currently conducts writing workshops internationally, focused on grief and healing. Her personal website is http://cathysosnowsky.com/ What I admire most about this woman is her courage in putting on paper, for the whole world to see, not just the sweet and sentimental stuff, but the gritty stuff, too. Her mistakes; her shortcomings: it's all in there. If you want to heal yourself, that's what you have to do: come clean. Writing's a bitch. If you don't believe me, try it yourself.

Labels: books, Cathy Sosnowsky, memoir, Snapshots, writing

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home