Banned in Boston

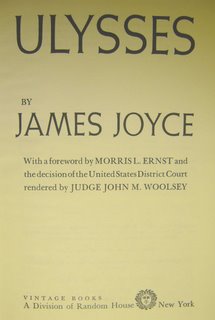

In preparation for Bloomsday, which is Friday, I'm re-reading James Joyce's Ulysses. I've got a nice hardbound Modern Library edition from 1961--a direct descendant of the 1934 first American edition. Besides the "complete and unabridged text," there's a foreword by Morris L. Ernst, a 1932 letter from James Joyce to Bennett Cerf, and "the monumental decision of the United States District Court rendered December 6, 1933, by Hon. John M. Woolsey lifting the ban on 'Ulysses.'"

In preparation for Bloomsday, which is Friday, I'm re-reading James Joyce's Ulysses. I've got a nice hardbound Modern Library edition from 1961--a direct descendant of the 1934 first American edition. Besides the "complete and unabridged text," there's a foreword by Morris L. Ernst, a 1932 letter from James Joyce to Bennett Cerf, and "the monumental decision of the United States District Court rendered December 6, 1933, by Hon. John M. Woolsey lifting the ban on 'Ulysses.'"Ulysses was famously banned from the United States in 1920 after one episode--involving masturbation--was published in an American literary magazine. In 1933, Random House challenged the ban by attempting to bring the book into the United States. Judge John Woolsey was assigned to the case.

Judge Woolsey writes as good a book review as I've ever read. In preparation for the case, he read the novel more than once and consulted with two friends "whose opinion on literature and life" he valued "most highly."

He concluded that Joyce was attempting "with astonishing success" to describe persons of the lower middle class living in Dublin in 1904 and describe not only what they did "but also to tell what many of them thought about the while....What he seeks to get is not unlike the results of a double or, if that is possible, a multiple exposure on a cinema film....To convey by words an effect which obviously lends itself more appropriately to a graphic technique, accounts, it seems to me, for much of the obscurity which meets a reader of 'Ulysses.'"

He further concluded that the use of the so-called "dirty words" could be justified by Joyce's sincerity and honesty, by the fact of their being "old Saxon words known to almost all men," and by the fact that "his locale was Celtic and his season spring."

Judge Woolsey properly defined the word "obscene" to mean leading "a person with average sex instincts" to sexually impure and lustful thoughts. He concluded that, "whilst in many places the effect of 'Ulysses' on the reader undoubtedly is somewhat emetic, nowhere does it tend to be an aphrodisiac."

Bravo Judge Woolsey!

A friend asked me the other day if I had a favorite century. I do: the 18th. It was the era of rationality. Of rationality and reasonableness, which sometimes seem to have vanished from our leadership, our founding fathers were shining examples: Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton, Franklin, Adams. And Judge Woolsey is a worthy heir.

1 Comments:

I mentioned this point during our wanderings through Worcester/Dublin yesterday, but may as well interject it here as well. The term "stream of consciousness," widely used for novels such as Ulysses, (or Mrs. Dalloway) seems to have begun as a borrowing from Principles of Psychology, by William James, the brother of a rather different sort of novelist.

In chapter 9 of Principles, the elder James brother wrote thus:

Consciousness, then, does not appear to itself chopped up in bits. Such words as 'chain' or 'train' do not describe it fitly as it presents itself in the first instance. It is nothing jointed; if flows. A 'river' or a 'stream' are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described. In talking of it hereafter, let us call it the stream of thought, of consciousness, or of subjective life.

Post a Comment

<< Home